Fast gamma radiation detectors are needed in a wide range of applications. We aim to use our fast detectors for material research (PALS) and in a second stage for medical imaging (TOF-PET).

Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy (PALS)

|

- Background - Microstructural imperfections are known to influence the mechanical, electrical and optical properties of materials. The origin of these imperfections can be manifold. For example, in semiconductors and insulators they may remain after deposition and ion-implantation processes typically applied to engineer layered structures with desired electrical and optical properties. In polymers the character of the imperfections, depend on the chemical and physical conditions during and after synthesis. Positron lifetime spectra are obtained by measuring the time between the injection of the positron in the sample and its subsequent annihilation.

|

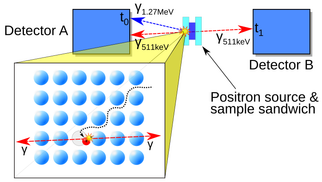

- State-of-the-art - In conventional lifetime experiments 22-Na is the isotope used as a positron source. Simultaneously with the positron a 1.274 MeV gamma quantum is emitted which acts as the start signal. The stop signal is derived from the detection of one of the corresponding 511 keV annihilation photons. Typical instrument response functions (IRF) have a width of ~200 ps, which is comparable to the positron lifetime in many materials and therefore imposes a fundamental limit on the accuracy of the method (best value: 145 ps [1]). With a pulsed positron beam 240 ps was achieved [2]. Only moderate source strengths can be used to avoid false coincidences. As a consequence, high detection efficiency is required to avoid that measurement times become excessively long.

Improving the time resolution to < 100ps will enable a better understanding and more precise identification of microstructural imperfections, which will push research on e.g. solar cell materials, energy storage and -conversion materials, materials for fusion reactors, and self-healing coatings.

Improving the time resolution to < 100ps will enable a better understanding and more precise identification of microstructural imperfections, which will push research on e.g. solar cell materials, energy storage and -conversion materials, materials for fusion reactors, and self-healing coatings.

- References -

[1] F. Becvar, J. Cizek, I. Prochazka, Apll. Surf. Sci. 225 (2008) 111-114.

[2] A. Calloni et al., J. Appl. Phys. 112 (2012) 024510.

[1] F. Becvar, J. Cizek, I. Prochazka, Apll. Surf. Sci. 225 (2008) 111-114.

[2] A. Calloni et al., J. Appl. Phys. 112 (2012) 024510.

Time-of-flight Positron emission tomography (TOF-PET)

|

- Background - PET complements computed tomography (CT) and nuclear magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which provide mainly anatomical information. PET/CT and PET/MR devices are routinely used to diagnose and stage cancer as well as for assessing the response to chemo- or radiotherapy. PET is a non-invasive imaging method that uses tiny amounts of radiotracer injected into patients to obtain quantitative images of the molecular functioning of the body.

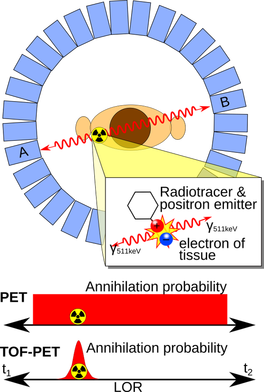

A PET system consists of a ring of detectors that measure pairs of annihilation quanta following the decay of positron emitting nuclei. These photons are emitted back-to-back (≈180°), see Figure. Thus, the origin of emission must be located along a line connecting the two detectors, i.e. the line of response (LOR). Tomographic images are reconstructed after collecting many LORs. Since the two annihilation photons travel at the speed of light, different lengths of the flight paths will lead to different arrival times at the respective detectors. This is used in TOF-PET for defining a localisation probability function constraining the location of the source to a small part of the LOR. The TOF method improves the statistical properties of the data by reducing ambiguity (i.e. noise), leading to better signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and, thereby, improved image quality. The benefit of using TOF information has been addressed by many research groups [3, 4, 5]. The main limiting factor in TOF is the uncertainty in the measurement of the arrival times of the two photons, leading to a residual uncertainty of the spatial localisation of the source along the LOR. |

- State-of-the-art - Several groups have studied the fundamental limits on the time resolution of scintillation detectors [6, 7, 8, 9]. Scintillator-related parameters of influence are the time profile of the scintillation pulse, the scintillation light yield, and variations in the optical propagation of the emitted scintillation photons as determined by the size, shape and surface properties of the scintillation crystal. The most important photosensor-related parameters are the photo-detection efficiency (PDE) and the single-photon time resolution (SPTR). L(Y)SO:Ce (possibly co-doped with Ca) is the material of choice in PET due to its good timing performance, high density and non-hygroscopic properties. PET detectors are often built from small scintillator “pixels”. The spatial resolution of such detectors is determined by the pixel size. TOF-PET systems with coincidence resolving time (CRT) in the range of 500-600ps FWHM and detection efficiency of about 40% are commercially available. Much better coincidence time resolutions of about 100ps FWHM have been achieved in laboratory [5, 10, 11]. However, these values were achieved using very small (~mm) crystals in which the influence of optical photon propagation is almost negligible. This, however, degrades the gamma detection efficiency to less than 5%. Such low efficiency is unacceptable in clinical PET as it leads to increased patient radiation-dose, prolonged examination times, and increased examination costs.

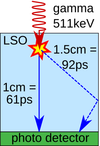

On the other hand, since optical photons need about 61 ps to traverse 1 cm in L(Y)SO, optical propagation imposes a fundamental bottleneck for achieving 100 ps CRT in large (~cm) crystals. TU Delft has shown that CRTs below 200ps FWHM in combination with high detection efficiency can nevertheless be achieved with a large, monolithic scintillator coupled to a so-called digital photon counter (DPC) array, using a maximum-likelihood approach to (partially) correct for the influence of scintillation photon propagation [12].

- References -

[3] M. Conti et al., Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Img. 38 (2011) 1147.

[4] J.Karp et al., JNM 49 (2008) 462.

[5] W.W. Moses, Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 580-2 (2007) 914.

[6] P. Lecoq et al., IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 57-5 (2010) 2411.

[7] S. Seifert et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 57-7 (2012) 1797.

[8] S.E. Brunner, PhD Thesis, Vienna UT (2014).

[9] S. Derenzo et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 59-13 (2014) 3261.

[10] S. Gundacker et al., Jour. Instr. 8-7 (2013) P07014.

[11] S. Seifert et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 55-7 (2010) N179.

[12] H.T. van Dam, Phys. Med. Biol. 58 (2013) 3243–3257.

[3] M. Conti et al., Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Img. 38 (2011) 1147.

[4] J.Karp et al., JNM 49 (2008) 462.

[5] W.W. Moses, Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 580-2 (2007) 914.

[6] P. Lecoq et al., IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 57-5 (2010) 2411.

[7] S. Seifert et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 57-7 (2012) 1797.

[8] S.E. Brunner, PhD Thesis, Vienna UT (2014).

[9] S. Derenzo et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 59-13 (2014) 3261.

[10] S. Gundacker et al., Jour. Instr. 8-7 (2013) P07014.

[11] S. Seifert et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 55-7 (2010) N179.

[12] H.T. van Dam, Phys. Med. Biol. 58 (2013) 3243–3257.